I regularly compete in CTFs as part of the team Samurai. For those of you unfamiliar with the concept, they’re essentially security contests which task the competitors with reverse engineering binaries, exploiting services, and breaking cryptography. The goal of each challenge is to find the flag —usually a file hidden on a server, or the result of cracking a ciphertext.

During this year’s 9447 CTF there was a neat challenge named HelloMike. The challenge read as follows:

The flag is 9447{$STR} where $STR is the shortest string that is accepted by this binary. If multiple accepted strings have the same length, you must use the lexicographically least such string.

Aside: If you’d like to follow along, install the latest version of Erlang/OTP, with HiPE.

Based on the hint and the extension, it looks like an Erlang executable. Let’s confirm:

$ file hellomike.beam

hellomike.beam: Erlang BEAM fileBefore we dive into the binary, let’s see what it does:

$ escript hellomike.beam

Usage: escript hellomike.beam YOURGUESS

$ escript hellomike.beam test

Thinking…

this{is not the flag}Based on the problem description, it seems like we need to find the shortest string that makes the program succeed — whatever that means. Our next step should be to reverse the binary and see what’s going on.

Erlang can be compiled with debugging symbols, which would make reversing the binary trivial. Let’s see if we can grab them.

$ erl

Erlang/OTP 17 [erts-6.1] [source] [64-bit] [smp:4:4] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false] [dtrace]

Eshell V6.1 (abort with ^G)

1> beam_lib:chunks(hellomike, [abstract_code]).

{ok,{hellomike,[{abstract_code,no_abstract_code}]}It looks like the binary wasn’t compiled with debug_info, so we’ll have to be more clever. Fortunately, Erlang/OTP ships with HiPE, the high-performance Erlang native code compiler. We can use it to disassemble the binary.

$ erl -noshell -eval ‘hipe:c(hellomike, [pp_beam]), init:stop().’ > hellomike.disasScanning through the resulting disassembly, we find the entry-point:

label 317:

{func_info,{atom,hellomike},{atom,main},1}

label 318:

{test,is_nonempty_list,{f,340},[{x,0}]}

{get_list,{x,0},{x,1},{x,2}}

{test,is_nil,{f,317},[{x,2}]}

{allocate_zero,6,2}

{move,{literal,”Thinking…~n”},{x,0}}

{move,{x,1},{y,5}}

{line,268}

{call_ext,1,{extfunc,io,format,1}}

{bif,self,nofail,[],{x,0}}

{move,{x,0},{y,4}}

{patched_make_fun,{hellomike,’-main/1-fun-0-’,1},69025816,1,0}

{line,269}

{call_ext,1,{extfunc,erlang,spawn,1}}

{test_heap,3,1}

{move,{x,0},{y,3}}

{put_tuple,2,{x,1}}

{put,{integer,0}}

{put,{y,5}}

{line,269}

sendThere’s a lot going on there, but the important thing to notice is that a process is being spawned with -main/1-fun-0- as its entry-point, and that the tuple {0, YOURGUESS} is being sent to it.

At this point we don’t know what -main/1-fun-0- is, so let’s dive into that part of the disassembly:

label 353:

{func_info,{atom,hellomike},{atom,’-main/1-fun-0-’},1}

label 354:

{call_only,1,{hellomike,nfa_0,1}}Based on the name, we’ll assume that nfa_0 is a nondeterministic finite automata. We could dive into the code behind it, but for now let’s step back and try to get a feel for what the program as a whole is doing.

Continuing from where we left off in the main function, we see the following:

label 319:

{loop_rec,{f,321},{x,0}}

{test,is_tuple,{f,320},[{x,0}]}

{test,test_arity,{f,320},[{x,0},2]}

{get_tuple_element,{x,0},0,{x,1}}

{get_tuple_element,{x,0},1,{x,2}}

{test,is_eq_exact,{f,320},[{x,2},{atom,success}]}

{test,is_eq_exact,{f,320},[{x,1},{y,3}]}

remove_message

{move,{atom,true},{x,0}}

{jump,{f,322}}

label 320:

{loop_rec_end,{f,319}}

label 321:

{wait_timeout,{f,319},{integer,1000}}

timeout

{move,{atom,false},{x,0}}This chunk of code is a little hard to follow without an Erlang background, but the gist of it is that the process blocks for 1 second, or until it receives a message. If that message is sent by the nfa_0 process we just spawned, and that message denotes a success, then we move true into register 0. Otherwise we move false into that same register.

Continuing along in main, we find 4 other such blocks of code, identical to the two we just analysed, except for the fact that they run the functions nfa_1, nfa_2, nfa_3, and nfa_4. Clearly we need to find some input that causes all 5 functions to succeed — and if the problem text is to be trusted, we must find the lexicographically smallest such input.

I won’t paste nfa_0 through nfa_4 here in their entirety, since each is about 800 lines long. Snippets of nfa_0 are worth looking at, however:

label 1:

{line,1}

{func_info,{atom,hellomike},{atom,nfa_0},1}

label 2:

{allocate_zero,2,1}

{move,{x,0},{y,1}}

{line,2}

...

...

...

label 5:

{get_tuple_element,{x,0},0,{x,1}}

{get_tuple_element,{x,0},1,{x,2}}

{test,is_integer,{f,56},[{x,1}]}

{select_val,{x,1},

{f,56},

{list,[{integer,4},

{f,6},

{integer,0},

{f,14},

{integer,1},

{f,23},

{integer,2},

{f,31},

{integer,3},

{f,43}]}}

label 6:

{test,is_nonempty_list,{f,13},[{x,2}]}

{get_list,{x,2},{x,3},{x,4}}

{test,is_integer,{f,56},[{x,3}]}

{select_val,{x,3},

{f,56},

{list,[{integer,51},

{f,7},

{integer,65},

{f,8},

{integer,70},

{f,9},

{integer,49},

{f,10},

{integer,67},

{f,11},

{integer,54},

{f,12}]}}

...

...

...

label 13:

{test,is_nil,{f,56},[{x,2}]}

remove_message

{test_heap,3,0}

{bif,self,nofail,[],{x,0}}

{put_tuple,2,{x,1}}

{put,{x,0}}

{put,{atom,success}}

{move,{y,1},{x,0}}

{line,9}

send

{deallocate,2}

return

...

...

...

label 56:

{loop_rec_end,{f,3}}

label 57:

{wait,{f,3}}The important thing to notice is that we essentially have two switch statements. The first, under label 5, seems to encode 5 different states, each pointing to another switch statement. State 4, for example, points to label 6, the second switch statement in the snippet above.

Tracing through the code, it becomes clear that our original guess about the nondeterministic finite automata was correct — the function simply iterates over each character in the input, transitioning states as needed. Label 13, reached when entering state 4 while at the end of the input string, sends our desired success message to the main process.

Our task then becomes to reverse engineer each of the five NFAs in the code to determine the lexicographically smallest string that matches under all of them.

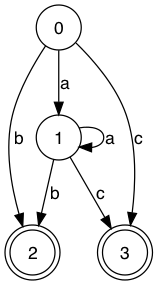

Aside: If you’re unfamiliar with NFAs, you can think of them as graph theoretic representations of regular expressions. For example, a*(b|c) would be represented as:

After reverse engineering the 5 NFAs, we get the following:

NFA0 = {

0 => {

1 => [48, 49, 50, 53, 54, 56, 65, 69]

},

1 => {

2 => [49, 50, 54, 55, 56, 57, 68]

},

2 => {

0 => [48, 49, 52, 53, 54, 66, 69],

1 => [48, 51, 53, 54, 66, 67, 70],

3 => [48, 52, 54, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70]

},

3 => {

4 => [48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 65, 66, 67, 69]

},

4 => {

2 => [51, 65, 70, 49, 67, 54],

:success => [‘’]

},

:success => {}

}

NFA1 = {

0 => {

1 => [50, 51, 53, 54, 55, 66, 67, 69],

2 => [48, 51, 53, 56, 57, 65, 66, 67],

4 => [48, 50, 51, 54, 55, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69]

},

1 => {

1 => [49, 51, 52, 53, 55, 66, 67, 69],

:success => [‘’]

},

2 => {

1 => [48, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56, 57, 65, 67, 69, 70],

3 => [49, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 69]

},

3 => {

0 => [48, 49, 53, 54, 55, 56, 66, 68, 70],

2 => [48, 49, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 57, 65, 66, 67]

},

4 => {

2 => [69, 70, 56, 49, 54, 68, 50],

:success => [‘’]

},

:success => {}

}

NFA2 = {

0 => {

1 => [50, 51, 52, 53, 54]

},

1 => {

2 => [49, 54, 55, 57, 68, 69],

3 => [50, 52, 54, 66],

:success => [‘’]

},

2 => {

0 => [55,51,68,56,52,57,65,53,54],

:success => [‘’]

},

3 => {

2 => [51, 53, 55, 56, 56, 66, 68, 69, 70],

3 => [48, 49, 51, 52, 56, 57, 68],

4 => [48, 49, 50, 53, 55, 56, 56, 65, 66, 69, 70],

:success => [‘’]

},

4 => {

1 => [48, 50, 51, 55, 56, 57, 69],

:success => [‘’]

},

:success => {}

}

NFA3 = {

0 => {

1 => [49, 50, 52, 53, 54, 56, 57, 65, 66],

:success => [‘’]

},

1 => {

4 => [49, 51, 52, 54, 56, 65, 68]

},

2 => {

0 => [49, 50, 51, 53, 56, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70],

1 => [48, 49, 53, 54, 57, 67, 68, 69],

3 => [48, 49, 52, 53, 57, 69, 70]

},

3 => {

1 => [48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 65, 67, 69, 70]

},

4 => {

0 => [48, 51, 54, 55, 65, 69, 70],

2 => [49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 65]

},

:success => {}

}

NFA4 = {

0 => {

1 => [49, 50, 53, 54, 56, 57, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70]

},

1 => {

2 => [49, 52, 53, 56, 65, 66, 67, 69]

},

2 => {

0 => [48, 49, 50, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57, 65, 67, 69, 70],

3 => [48, 50, 51, 67, 69],

:success => [‘’]

},

3 => {

1 => [51, 52, 54, 65, 68, 69, 70],

4 => [48, 52, 53, 57, 66, 67, 68, 70]

},

4 => {

0 => [48, 49, 53, 55, 67, 68]

},

:success => {}

}I’ve chosen to represent each NFA as a Ruby hash. NFA[initial_state][final_state] is an array denoting the transitions from initial_state to final_state.

From here, our goal is to find an input which will be matched by all 5 NFAs. We can do this by finding the intersection of the NFAs. It’s not the greatest code, but I hacked up some Ruby to calculate this intersection for me:

def intersect(a, b)

result = {}

result[:success] = {}

a.keys.product(b.keys).each do |state|

new_state = state.flatten

if new_state.any? { |s| s == :success }

next

end

a[state[0]].keys.product(b[state[1]].keys).each do |transition|

new_transition = transition.flatten

if transition.all? { |t| t == :success }

result[new_state] ||= {}

result[new_state][:success] = ['']

next

end

transitions = a[state[0]][transition[0]] &

b[state[1]][transition[1]]

if !transitions.empty?

result[new_state] ||= {}

result[new_state][new_transition] = transitions

end

end

end

result

end

intersection = [NFA0, NFA1, NFA2, NFA3, NFA4].reduce { |a,b| intersect(a, b) }At this point, we can simply perform a breadth-first-traversal over intersection, to find the first input which results in a state of :success.

The BFS code is left as an exercise, but running it should return the transitions [50, 49, 52, 53, 49, 51, 54, 52, 49, 49, 53, 55, 54, 65]. Converting to ascii gives us the string “2145136411576A”. Let’s test our answer:

$ escript hellomike.beam 2145136411576A

Thinking…

This matches, but is this the lexicographically smallest shortest string? ;)The CTF is over now, but submitting 9447{2145136411576A} as a flag resulted in a successful submission!

If you enjoyed this problem, I recommend giving CTFs a try for yourself. There’s one every week or two, and they’re all listed in one place, on CTF Time.

Thanks to 9447 for running an awesome contest this year!